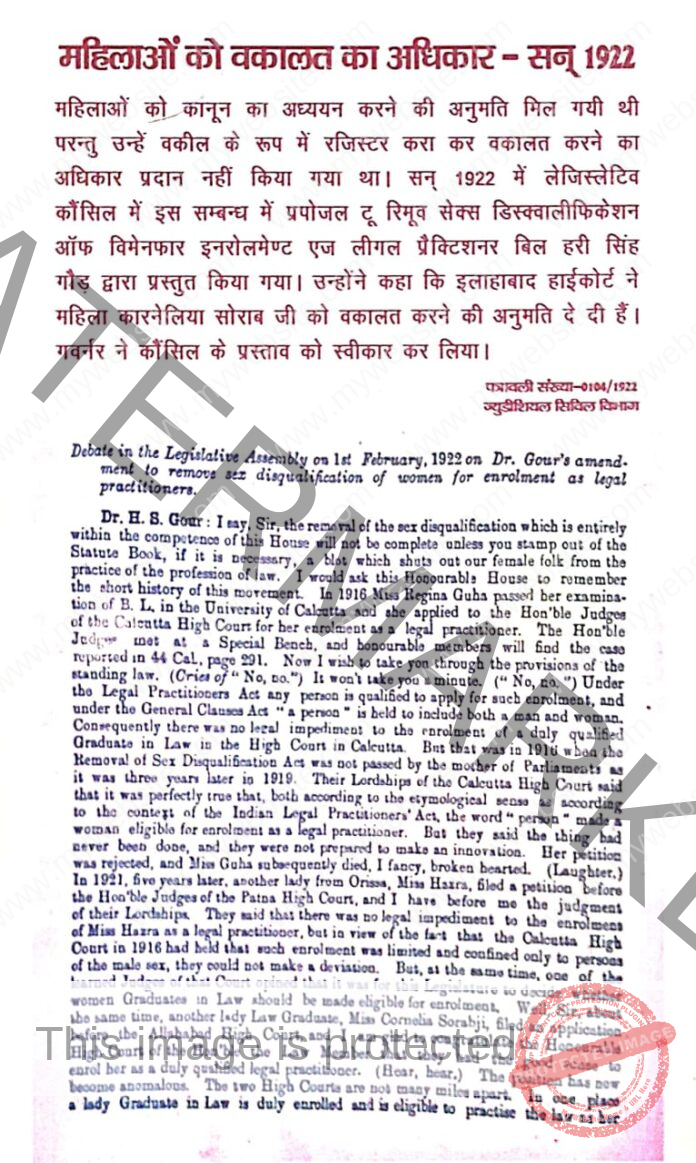

Over a century ago, on February 01, 1922, Dr Hari Singh Gour, a distinguished lawyer and Deputy President of the Central Legislative Assembly of British India, in his speech in Legislative Assembly, had vociferously said “the removal of the sex disqualification which is entirely within the competence of this House will not be complete unless you stamp out of the Statute Book, if it is necessary, a blot which shuts out our female folk from the practice of the profession of law.”

As per records of the Legislative Assembly, preserved in the Regional Archives, Prayagraj, Gour had narrated previous incidents wherein women law graduates were denied permission to practice law.

During the debate on the issue in Legislative Assembly he had said, “In 1916 Miss Regina Guha passed her examination of B.L. in the University of Calcutta and she applied to the Hon’ble Judges of the Calcutta High Court for her enrolment as a legal practitioner. Under the Legal Practitioners Act any person is qualified to apply for such enrolment, and under the General Clauses Act “a person” is held to include both a man and woman. Consequently there was no legal impediment to the enrolment of a duly qualified Graduate in Law in the High Court in Calcutta. But that was in 1916 when the Removal of Sex Disqualification Act was not passed by the mother of Parliaments as it was three years later in 1919.”

Gour, also a Member of the Indian Central Committee associated with the Royal Commission on the Indian Constitution (popularly known as the Simon Commission), continued to further state, “Their Lordships of the Calcutta Court said that it was perfectly true that, both according to the etymological sense as according to the context of the Indian Legal Practitioners’ Act, the word “person” made a woman eligible for enrolment as a legal practitioner. But they said the thing had never been done, and they were not prepared to make an innovation. Her petition was rejected, and Miss Guha subsequently died, I fancy, broken hearted.”

As per over a century old records bearing mute testimony to the ordeal of qualified women, struggling to make space for themselves in legal profession, Dr Gour further mentioned in his speech, “In 1921, five years later, another lady from Orissa, Miss Harsa, filed a petition before the Hon’ble Judges of the Patna High Court, and I have before me the judgement of their Lordships. They said that there was no legal impediment to the enrolment of Miss Harsa as a legal practitioner, but in view of the fact that the Calcutta High Court in 1916 had held that such enrolment was limited and confined only to persons of the male sex, they could not make a deviation. But, at the same time, one of the learned Judges of that Court opined that it was fit for this Legislature to decide whether women Graduates in Law should be made eligible for enrolment.”

However, in the end of his speech he says, “Well, Sir, about the same time, another lady Law Graduate, Miss Cornelia Sorabji, filed an application before the Allahabad High Court, and I am told that she was enrolled. The Honourable High Court of the Hon’ble Law Member felt that they had the good sense to enroll her as a duly qualified legal practitioner.”

This was the beginning of women stepping into the legal profession in India. Cornelia Sorabji, an Indian lawyer, social reformer and writer was not only the first female graduate from Bombay University, and the first woman to study law at Oxford University but she also became the first woman advocate in India, not be recognized as a barrister until the law which barred women from practicing was changed in 1923.

Many may not know but it was the Allahabad High Court, which first witnessed a woman enter the legal profession in India.

However, post 102 years, when the first woman stepped into the otherwise male bastion in 1923, the scenario has changed completely.

As per data made available by the Bar Council of India, a statutory body established under the Advocates Act, 1961, entrusted with the responsibility of regulating legal education and the legal profession in India, a total of 2,36,403 candidates registered for the All India Bar Examination-XIX (AIBE-XIX) held in the month of December, 2024 out of which 82,402 were female candidates, constituting 34.85% of total examinees. This trend reflects a steady participation of women in the post-qualification examination process and indicates a sustained interest in Law as a career.

While there is no statutory reservation under the Advocates Act, 1961, several Central and State Universities, as well as National Law Universities (NLUs), have taken independent initiatives to promote legal education among women.

These include merit-cum-means scholarships for female candidates, fee concessions, hostel subsidies, and the development of gender inclusive campuses. In some public universities, a limited number of seats are reserved for women under institutional quotas, facilitated by the enabling power of Article 15(3) of the Indian Constitution. Additionally, women focused legal awareness programmes are being conducted in rural and semi urban regions to improve access and motivation for legal education.